Mikhail Bakhtin 1895-1975

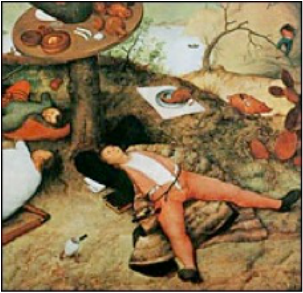

Brueghel, Pieter the Elder

The Fight between Carnival and Lent

Brueghel, Pieter the Elder

The Fight between Carnival and Lent

Rabelais and His World. Translated by H. Iswolsky.

Bloomington: Indiana Press, 1984 [1965].

Bakhtin’s great book on medieval carnival was and remains the Radical Anthropology Group's (RAG) bible. Below are some extracts, lightly edited and abridged. If you’re a pedant needing scholarly accuracy including page numbers, view PDF file.

‘The basis of laughter which gives form to carnival rituals frees them completely from all religious and ecclesiastic dogmatism, from all mysticism and piety. They are also completely deprived of the character of magic and prayer; they do not command; nor do they ask for anything. These forms of ritual based on laughter, which existed in all the countries of medieval Europe, offered a completely different, nonofficial, extraecclesiastical and extrapolitical aspect of the world and of human relations. They built a second world and a second life outside officialdom, a world in which all medieval people lived during a given time of the year. Initially, before the establishment of class society and politics, it seems that the serious and the comic aspects of the world and of the deity were equally sacred, equally “official.” Such equality was preserved in rituals of a later period of history. For instance, in the early period of the Roman state, the ceremonial of the triumphal procession included on almost equal terms the glorifying and the deriding of the victor. The funeral ritual combined lamenting (glorifying) with derision of the deceased. Only once the class hierarchy had become definitely consolidated did all this become impossible. All the comic forms were transferred, some earlier and others later, to a nonofficial level.

Pieter Bruegel's

Conflict between Carnival and Lent

Pieter Bruegel's

Conflict between Carnival and Lent

Certain carnival forms would parody the Church’s cult. All these forms were systematically placed outside the Church and religiosity, pertaining to an entirely different sphere. Because of their obvious sensuous character and their strong element of play, carnival images closely resemble certain artistic forms. But the basic carnival nucleus of this culture is by no means a purely artistic form; nor is it a spectacle. It does not, generally speaking, belong to the sphere of art. It belongs to the borderline between art and life. In reality, it is life itself, but shaped according to a certain pattern of play. In fact, carnival does not know footlights, in the sense that it does not acknowledge any distinction between actors and spectators. Footlights would destroy a carnival, as the absence of footlights would destroy a theatrical performance.

Pieter Brueghel's

Wedding Dance

Pieter Brueghel's

Wedding Dance

Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people. While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is, the laws of its own freedom. It has a universal spirit; it is a special condition of the entire world, of the world’a and renewal, in which all take part. Such is the essence of carnival, vividly felt by all its participants. It was most clearly expressed and experienced in the Roman Saturnalias, perceived as a true and full, though temporary, return of Saturn’s golden age upon earth. The tradition of the Saturnalias remained unbroken and alive in the medieval carnival, which expressed this universal renewal and was vividly felt as an escape from the usual official way of life. Clowns and fools are characteristic of the medieval culture of humour. They were the constant, accredited representatives of the carnival spirit in everyday life out of carnival season. They stood on the borderline between life and art….

Thus carnival is the people’s second life, organized on the basis of laughter. The feast (every feast) is an important primary form of human culture. It cannot be explained merely by the practical conditions of the community’s work, and it would be even more superficial to attribute it to the physiological demand for periodic rest. The feast had always an essential, meaningful philosophical content. No rest period or breathing spell can be rendered festive per se; something must be added from the spiritual and ideological dimension. They must be sanctioned not by the world of practical conditions but by the highest aims of human existence, that is, by the world of ideals. Without this sanction there can be no festivity.

Peasant Wedding

Peasant Wedding

The feast is always essentially related to time, either to the recurrence of an event in the natural (cosmic) cycle, or to biological or historic timeliness. Moreover, through all the stages of historic development feasts were linked to moments of crisis, of breaking points in the cycle of nature or in the life of society and man. Moments of death and resurrection, of change and renewal always led to a festive perception of the world. These moments, expressed in concrete form, created the peculiar character of the feasts. In the framework of class and feudal political structure this specific character could be realized without distortion only during carnival time and similar marketplace festivities. They were the second life of the people, who for a time entered the Utopian realm of community, freedom, equality, and abundance.

The Swiss Guard. Papal Rome.

The Swiss Guard. Papal Rome.

By contrast, the official feasts of the Middle Ages, whether ecclesiastic, feudal or sponsored by the state, did not lead the people out of the existing world order. They created no second life. On the contrary, they sanctioned the existing pattern of things and reinforced it. The link with time became formal: changes and moments of crisis were relegated to the past. Actually, the official feast looked back at the past and used the past to consecrate the present. Unlike the earlier and purer feast, the official one asserted all that was stable, unchanging, perennial: the existing hierarchy, the existing religious, political, and moral values, norms, and prohibitions. It was the triumph of a truth already established, the prevailing truth asserted as eternal and indisputable. This is why the tone of the official feast was monolithically serious and why the element of laughter was alien to it. The true nature of human festivity was betrayed and distorted.

Britain's Trooping of the Colour at

St.James' London

Britain's Trooping of the Colour at

St.James' London

But this true festive character was indestructible; it had to be tolerated and even legalized outside the official sphere . It was turned over to the popular sphere of the marketplace. As opposed to the official feast, one might say that carnival celebrated temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions.

Carnival was the true feast of time, the feast of becoming, change, and renewal. It was hostile to all that was immortalized, all that was finished and complete.

Carnival was the true feast of time, the feast of becoming, change, and renewal. It was hostile to all that was immortalized, all that was finished and complete.

Anglican Clergy

Anglican Clergy

Rank was especially evident during official feasts; everyone was expected to appear in the full regalia of his calling, rank, and merits, occupying the place appropriate to his position. It was a consecration of inequality. By contrast, all were considered equal during carnival. Here, in the town square, a special form of free and familiar contact reigned among people who were otherwise divided by barriers of caste, property, profession, and age. People were, so to speak, reborn for new, purely human relations.

Notting Hill Carnival, London

Notting Hill Carnival, London

This temporary suspension, both ideal and real, of hierarchical rank created a special type of communication, not possible in everyday life. The experience demanded ever changing, playful, undefined forms. All the symbols of the carnival idiom are filled with this pathos of change and renewal, with the sense of the gay relativity of prevailing truths and authorities. We find here a characteristic logic, the peculiar logic of the “inside out” (à l’envers), of the “turnabout,” of a continual shifting from top to bottom, from front to rear, of numerous parodies and travesties, humiliations, profanations, comic crownings and un-crownings. A second life, a second world of folk culture is thus constructed; it is to a certain extent a parody of the extracarnival life, a “world inside out.”

Notting Hill Carnival, London

Notting Hill Carnival, London

Bare negation is completely alien to folk culture. Folk humor denies the social order, yet revives and renews it at the same time. So carnival laughter is complex. It is, first of all, a festive laughter. It’s by no means an individual reaction to some isolated “comic” event. Carnival laughter is the laughter of all the people. Second, it is universal in scope; it is directed at all and everyone, including the carnival’s participants. The entire world is seen in its droll aspect, in its gay relativity. Third, this laughter is ambivalent: it is gay, triumphant, and at the same time mocking, deriding. It asserts and denies, it buries and revives. Such is the laughter of carnival.

Pieter Brueghel

Pieter Brueghel

The people’s festive laughter is directed not only at others but also at those who laugh. The people do not exclude themselves from the wholeness of the world. They, too, are incomplete. They also die and are revived and renewed. This distinguishes the people’s festive laughter from the pure satire of modern times. The satirist whose laughter is negative places himself above the object of his mockery. He is opposed to it. The wholeness of the world’s comic aspect is destroyed, and that which appears comic becomes a private reaction. The people’s ambivalent laughter, by contrast, expresses the point of view of the whole world; he who is laughing also belongs to that world.